Panorama

Origins. The age of the silent film

The first demonstration of the Cinématographe Lumière took place in Barcelona on December 20th 1896. A similar demonstration had also taken place shortly before in Madrid, and of course initially in Paris (on December 28th 1885). The event was held at a photographer’s store called Napoleón situated on La Rambla, the city’s central boulevard. Both before and after these dates presentations took place of other inventions linked to what was to become known as the cinema, such as the famous “magic lanterns”, but all attracted at the time more scientific than artistic interest. They were simple images in movement that aroused nothing more than curiosity, and nobody could imagine any particular future potential for them. The first filmings in Catalonia were undertaken by Fructuós Gelabert, an inventor and apprentice filmmaker, now considered the founder of Catalan and Spanish cinema. In 1897, after making several documentaries, Gelabert shot the first Spanish fiction movie, Riña en un café (“Brawl in a café”). He went on to create the Films Barcelona production company, and to adapt theatre plays such as Terra Baixa (1907) and Maria Rosa (1908). Other Catalan filmmaking pioneers were Albert Marro and Ricardo de Baños, who with their production company Hispano Films made films based on both contemporary subjects and literary adaptations, with titles such as Don Juan Tenorio (1908), Don Joan de Serrallonga (1910), The Justice of King Philip II (1910) and Don Pedro the Cruel (1912), thus following in the footsteps of recent Italian experiences with artistic films. One of the great names of the day, and together with the Frenchman Georges Méliès one of the first true film innovators, was Segundo de Chomón, a man of prodigious imagination and technical resources, who shot in Catalonia between 1902 and 1905 films that explored the full potential of the cinema and included highly surprising trick sequences, a prime example being El hotel eléctrico (“The electric hotel”, 1905). His genius, internationally recognized, was fundamental in pointing the way for the future of filmmaking. From 1908 onward, what had started out as a simple form of amusement began to become a popular spectacle, and the powers that be, anxious about its possible influence, felt the need to react, with the result that various forms of censorship started to appear. Filmmakers gave people what they liked and what normally came from the theatre and literature, i.e., melodramas, comedies and popular operettas. Francesc Gelabert dazzled the public with titles such as Corazón de madre (“A mother’s heart”, 1908) and Amor que mata (“Love that kills”, 1908). By 1914, Barcelona had become the capital of the Spanish film world, the production centre for the country’s entire movie industry and one of the cities with the largest number of movie theaters in the world (140), coming behind only New York and Paris. Intellectuals turned their backs on the film world – a phenomenon that has since lost force but still continues today – but one of them, Adrià Gual, founded the Barcinógrafo production company in 1914, through which he produced classics such as El alcalde de Zalamea (“The Mayor of Zalamea”) and La gitanilla (“The little gypsy girl”) (both in 1914). The First World War led to a fall in production and after the war both Catalan and Spanish cinema began to copy the trends which were then enjoying success all over the world. Comic films, serials, melodramas, historical movies: the aim was to try to make money offering the formulas which were bringing in money at the box-office for films from other countries. The first “movie buffs” started to appear, people who could see further, who believed in a different future, that of a “seventh art”: Guillermo Díaz-Plaja and Josep Palau founded the Mirador, the first film club in Spain. Santiago Rusiñol was soon to head another one. In 1928 a manifesto for avant-garde films was issued by the group L’Amic de les Arts (“The Friends of Art”), whose members included among others Sebastià Gasch and Salvador Dalí. The Spanish Republican government showed no interest in the film industry, quite the opposite, in fact, since it slapped heavy taxes on it and completely failed to protect it. Moreover, the high costs of introducing the talkies due to the need to convert movie theaters made the situation even more serious. Nevertheless, progress is not to be stopped, and Catalonia continued to be the driving force behind the Spanish film industry. The new technology also began in Barcelona, and in January 1929 local director Amic brought out his film Les Caramelles (“Folksongs”), with sound provided by the Parlophone system, based on synchronized records and used for The Jazz Singer. The same director, who was not happy with the result obtained, recorded the song El noi de la mare (“Mother’s Boy”), sung by Raquel Meller, using the American Western Electric system. At the end of the year the half-length films La España de hoy (“Today’s Spain”) and Cataluña (“Catalonia”) were released, with sound provided by the Filmófono system, an adaptation of the German Tobis-Klangfilm technique.

The Spanish Republic. The “Talkies”

The first years of the new invention led to the inevitable experiments with this new toy that urgently required an “instruction manual” to clarify the ideas of those working in the industry. The historical events that were soon to follow at an accelerated pace did not exactly give very much time for reflection to discover what forms of expression Catalan talking films could adopt. The same thing happened all over the world, but Hollywood in particular reacted the fastest, exploring the possibilities of a new universe in which sound could become the essential dramatic element as a complement to film images. In this sense it seemed logical that the local film industry should simply produce “talking” adaptations of silent films, as was in fact happening all over the rest of the world, using the potential of sound only to allow characters to speak, and not thinking of sound as a distinct form of artistic expression. An example of this approach is El Nandu va a Barcelona (“Nandu goes to Barcelona”, 1931), by Baltasat Abadal, a musical comedy apparently inspired by the Catalan musical revue Que és gran Barcelona (“How big is Barcelona!”), about a country boy called Nandu who visits the big city, with all the contrasts between rural and city life.

In 1932 the French producer Camille Lemoine , one of the founders of the French production company Orphéa Film, set up the Orphea studios with the encouragement of Francisco Elías, located behind what had been the Hall of Chemistry at the Barcelona Universal Exhibition held in the Montjuic district of the city in 1929. The firm subsequently expanded its activities to become a full-blown production company. Its first production was Pax, a pacifist fable directed by Elías himself and released in French since he could not find financing to bring it out in either Catalan or Spanish. José Buchs directed Carceleras (“The women jailers”), the first full talking film with all dialogue and accompanying songs in Spanish. At that time other productions were not yet full talking films in their entirety, as is demonstrated by examples such as El último día de Pompeyano (“The last day of Pompeianus”, by F.Elías) and El sabor de la gloria (“Taste of glory”, by F.Roldán). Thanks to Orphea, Barcelona again became the film capital of Spain. All Spanish film production in 1932 and 1933 came from the Orphea Studios. On February 7th 1936, during the filming of Elías’ Maria de la O, a fire broke out on set which destroyed the studios, which were not to be rebuilt until after the Spanish Civil War. It was only with El café de la Marina (directed by Domènec Pruna, 1933), the first full-length talking film in Catalan, that we find a true native Catalan film (of which a Spanish-language version was also made, only finally released in Madrid in 1941). This was an extremely ambitious project financed by a section of the cultivated Catalan middle class, but, despite the generosity of its budget it came up against financial difficulties and it was necessary to finish it very hastily. It was in fact an enormous commercial flop, a fact which inevitably discouraged potential investors to the detriment of the production of fiction films in Catalan and leading to the consolidation of Spanish cliché-ridden productions and popular operettas. The author of the theater play on which the movie was based took part in the filming, which ensured that the movie would retain the sociological aspects of the original play, which was a portrait of the incredible poverty and misery to be found at the time in the Costa Brava region, which made its inhabitants dream of emigrating to the Americas. The plot turns around the story of Caterina, the daughter of the owner of the café, who is obliged to have an abortion after being abandoned by her cynical fiancé, and resigns herself to accepting a marriage of convenience with a rich man from Banyuls, on the French side of the frontier. All the copies of the film were destroyed in a fire, so that its value can only be assessed through journalists’ reports of the day. The period of the Spanish Second Republic had certainly consolidated Barcelona as the undisputed capital of the Spanish film industry, but the majority of the productions, filmed as they were by directors from other countries or from the rest of Spain, did not deal with subjects that were truly Catalan, but rather contented themselves with turning into talking pictures stories or subjects that were more or less the same as those that had enjoyed success during the period of the silent films. Catalonia as a source of subject-matter continued to be absent from most of the Catalan movies filmed in Barcelona.

Even if it is only for its documentary aspects, we should mention Boliche (by Francisco Elías, 1933), which showed many different parts of the city of Barcelona, including aerial views filmed from the cable-car over the port. The film reflected the phenomenon of the trio of Argentinian singers Irusta, Fugazot and Demare, who enjoyed tremendous success at that time in the Barcelona music-halls. Also worthy of interest was Barrios bajos (“Poor neighborhoods”, by Pedro Puche, 1937), produced during the Spanish Civil War by the S.I.E. (Entertainment Industry Syndicate), the anarcho-syndicalist production organism, and a film that revealed unexpected aspects of the poor districts of Barcelona through a passionate melodrama and suspense-filled plot that can to some extent be considered to lay the basis for the future neo-realism of the Italian cinema. The film also surprised by some of its love scenes, which were considered daring at the time, but today would be considered as totally innocent.

One of the most representative films of the Barcelona of the Civil War period, however, was Aurora de esperanza (“Dawn of hope” by Antonio Sau, 1936-1937), also produced by the S.I.E., and which at the time was considered as a first attempt to produce socially committed cinema and the country’s first truly revolutionary film. The plot exposes the situation of the working class during that difficult period of conflict, and becomes by turns a defense of the anarcho-syndicalist ideology, an attack on the injustices of capitalism, and an affirmation of the need to become involved in the armed struggle against fascism. While the fiction movies produced at the time were few and far between, the opposite was the case for the production of documentaries and news bulletins, through which a large part of the conflictive second half of the decade can be reconstructed. The Civil War encouraged the emergence of a Catalan documentary film with an urgent message, used to provide information but also as an educational tool to raise the awareness of the population at large. Madrid also served as a center of production for the rest of the remaining Republican zone of the Spanish territory, but here in Barcelona, apart from the official syndicates, particularly noteworthy was the role of Laya Films, the filmmaking section of the Catalan Autonomous Government’s Commissariat for Propaganda, created in 1936 and dedicated to the production and distribution of films, under the directorship of Joan Castanyer. Its most representative production, Espanya al dia (“Spain day by day”) consisted of 60 weekly news programs. 1938 saw the creation of Catalonia Films, an organism that was fully integrated in the Catalan government’s administrative structure, and which was charged with boosting national film production. The end of the Civil War meant the disappearance of all these institutions and the Catalan film industry, like everything else, fell into the hands of the winners of the conflict.

The Franco regime. The muzzling of freedom of expression

Immediately after the entry into Barcelona of General Franco’s troops, the Catalan film industry was expropriated by the victorious forces. They quite simple dismantled it. In accordance with the orders given under the so-called “Special Regime of Occupation”, all the basic parts of film production industry were confiscated. Movie theaters were closed, and were only reopened thirty days later. For a decade, due to the cinema’s status as popular art by definition, the fascist regime controlled the film sector with an iron hand, employing censorship, blacklists, subsidies for favorable projects, etc., and also, with the same logic, prohibiting any form of nationalist expression on the part of the various historical cultural and linguistic communities within the Spanish territory. The situation remained practically unchanged until nearly the end of the decade of the 1940s, when the Franco regime was obliged to ease the conditions somewhat as a result of the defeat of Germany and Spain’s subsequent admission into certain international organisms.

Catalonia did not regain the level of filmmaking activity that it had enjoyed during the Republican period until 1942. Ignacio F. Iquino, the most prolific producer and director in the Catalan film industry, first worked for the national film company CIFESA making amusing little comedies that show his great grasp of the medium, producing films such as ¿Quién me compra un lio? (“Who wants to buy a date from me?”, 1940), El difunto es un vivo (“The deceased is alive”, 1941) and Boda accidentada (“An eventful wedding”, 1942), before going on to create in 1942 Emisora Films, where he made an international type of movie that was completely different from the type of film being made at the time in Spain, with titles such as Hombres sin honor (“Men without Honor”, 1944), Cabeza de hierro (“Iron head”, 1944), Noche sin cielo (“Night without sky”, 1947) and El tambor del Bruch (“Bruch’s drum”, 1948). Iquino went on to found I.F.I. in 1948, and Emisora was to make that same year En un rincón de España (“Somewhere in Spain”, directed by Jerónimo Mihura and undoubtedly prepared by Iquino), the first color movie with a Spanish patent, that of the short-lived Cinefotocolor. Other famous directors from this period are Miquel Iglesias for Adversidad (“Adversity”), the first adaptation at this period of a Catalan classic novel (Solitud), Llorenç Llobet-Gràcia for Vida en sombras (“Life in the shadows”, 1947-1948), and Ricard Gascón for Don Juan de Serrallonga (1948), not forgetting the full-length animated feature film Garbancito de la Mancha (1942-45, Arturo Moreno, Armando Tosquellas and José María Carnicero), the first European color animated production, a major commercial and artistic venture that was highly unusual for the Spain of this time. In 1950, two films were the first examples of Barcelona crime movies: Brigada criminal, by Ignacio F. Iquino, and Apartado de Correos 1001 (“P.O. Box 1001”, by Julio Salvador), a native genre that was completely different from the films being made in Madrid, and which has continued up to the present day with the logical variations over time. Other outstanding examples of movies of this kind over the years were El cerco (“Police cordon” by Miquel Iglesias, 1955), Distrito quinto (“District No. 5”, 1957) and Un vaso de whisky (“A glass of whisky”, 1958), both by Julio Coll, A sangre fria (“In cold blood” by Joan Bosch, 1959), Los atracadores (“The robbers” by Francesc Rovira Beleta, 1961) and A tiro limpio (“A clear shot” by Francesc Pérez Dolç, 1962). Made with very limited means, filmed in natural settings and based on real criminal cases, this genre had its own “star system” and benefited from a pleasant, direct and spectacular style. It was nonetheless necessary at times to take great care to ensure that the censors did not realize that the figures of some common criminals concealed allusions to politicians whom the regime considered as outlaws.

In 1962 the Orphea Studios disappeared as the result of a fire, but their activity in Barcelona continued. In 1963, Rovira Beleta’s Los Tarantos was nominated for an Oscar for Best Foreign Film. In 1965 the Balcázar family created in the suburb of Esplugues del Llobregat their own studios (soon given the nickname of “Esplugues City”), where they developed the production of popular movies, especially Westerns, at a time of great popularity for this type of film which was to continue until the end of the following decade. Most of the local directors of the day established themselves here to help their commercial survival, including Joan Bosch, Miquel Iglesias, Alfons Balcázar, Ignacio Iquino, etc. It was here that Isasi Isasmendi made two international productions with well-known names from world cinema, Estambul 65 (“That man in Istanbul”) and Las Vegas 500 millones (“They came to rob Las Vegas”, 1968), which were immediately widely imitated. Joan Bosch showed Spanish cinema’s first bikini and started the country’s fashion for beach movies with Bahia de Palma (“Palma Bay”, 1962). Other directors attempted to make socially committed films to reflect the realities of national life, such as Pere Balañá with El último sábado (“The last Saturday”, 1966), Jaime Camino with Los felices 60 (“The Swinging Sixties”, 1964), Julio Coll with Los cuervos (“The Crows”, 1961), Josep Maria Font with Vida de familia (“Family life”, 1963) and Josep Maria Forn, who, while adapting the novel M’enterro en els fonaments (“Buried in the foundations”, 1968-69) had such serious problems with the Franco regime’s censors that, since he refused to accept the changes they imposed, he was only able to release the film in 1984, when it came out with the title La Respuesta (“The Reply”). By this time the use of the Catalan language had slowly started to be allowed again, leading to the appearance of films such as Maria Rosa (by Armand Moreno, 1964) and En Baldiri de la Costa (by Josep Maria Font Espina, 1968).

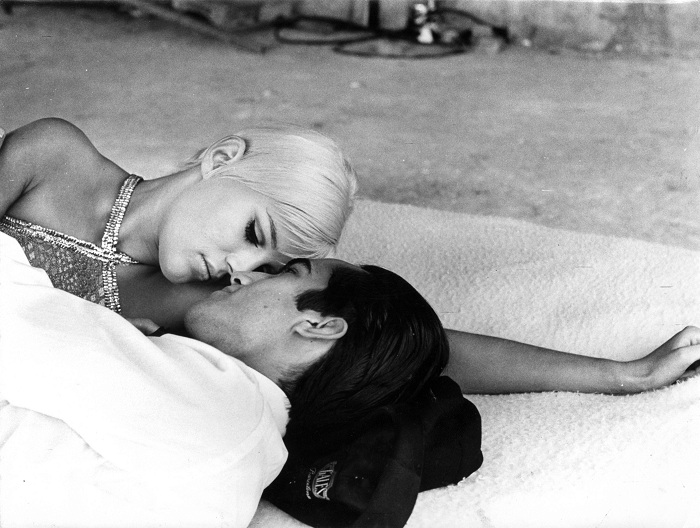

Between 1965 and 1968 Barcelona witnessed a series of films of an experimental nature, thanks to the inauguration of a new cinema law promoted by García Escudero favoring this type of film, and also thanks to the personal finances of most of the directors concerned, since few of them would recover their costs at the box-office. Although it did not at the time see itself as a clearly-defined movement, the magazine Fotogramas decided to present them as a coherent group which it called the Barcelona School and came to include filmmakers such as Pere Portabella, Carles Duran, Gonzalo Suárez, Jacinto Esteva, José Maria Nunes, Vicente Aranda and Joaquim Jordà. The films that define them were, among others, Fata Morgana, Noches de vino tinto, Dante no es únicamente severo, Ditirambo, Nocturn 20, Biotexia, No compteu amb els dits, Cada vez que.., Libertina 70, Vampyr-Caudecuc, Esquizo and Después del diluvio. It was the same Garcia Escudero law that led to the appearance of what came to be known as the New Spanish Cinema, a type of filmmaking at the opposite end of the spectrum from the Barcelona School, and in which a social or political message normally predominated over aesthetic experimentation. La piel quemada (“Burned skin” by Josep Maria Forn, 1967) is one of the few Catalan films that can be included in this category, and is one of the best films that have been made in Spain on the subject of the human and social problems caused by immigration from one region of the country to another. The New Spanish Cinema had a greater influence in Madrid (where it was sometimes called el cine mesetario or “the cinema of the plain of Castile”), with directors such as Miguel Picazo, Carlos Saura, Julio Diamante and Basilio Martin Patino.

During the final years of the Franco regime, filmmaking in Catalonia followed the pattern of Spanish cinema as a whole (which was entirely logical, given the official financial dependence and the lack of political autonomy), seeking the weak points in the official censorship to make commercial films of low quality and high erotic content, although also testing the limits with films on more important subjects. The sense of disorientation of the official censors continued into the first few years of the transition to democracy, but finally entering a state of normality, with all obstacles removed.

Filmmaking in democratic Spain. Freedom!

Without obstacles of any kind, films such as La ciutat cremada (“The burned city” by Antoni Ribas, 1976) and Companys procés a Catalunya (“The trial of Lluís Companys in Catalonia” by Josep Maria Forn, 1979) were shown at movie theaters for long periods of time, becoming true social phenomena. Movie-goers were deeply moved, and many wept openly. Films started to be made dealing with the Spanish Civil War from the point of view of the losing side, such as Las largas vacaciones del 36 (“Long vacations of ’36”, 1976) and La vieja memoria (“The old memory”, 1978), both by Jaime Camino. La ràbia (“Rage” by Eugeni Anglada, 1978) and Alícia en la España de las maravillas (“Alice in Spanish Wonderland” by Jordi Feliu, 1978) were extremely innovative and committed films. From now on, everything was possible, and films could be made in Catalonia with total freedom of expression, as was the case in the rest of Spain.

The proof can be seen in the work of Francesc Bellmunt, Francesc Betriu, Ventura Pons, Bigas Luna, Vicente Aranda, Antonio Chavarrias, Antoni Verdaguer, Gonzalo Herralde, Rosa Vergés, Isabel Coixet, Judith Colell, Carles Benpar, Jesús Garay... and many, many more. Such directors made all kinds of films, both commercial and experimental. A new Catalan cinema has been created, with a true local identity, and exporting films to different countries and festivals all over the world, with a variety of different titles and objectives, films made by José Luis Guerín, Marc Recha, Jaume Balagueró, Albert Serra, José Antonio Bayona, Agustí Villaronga, Cesc Gay, Manuel Huerga and Joaquim Oristrell. There is a generation of young people who are bringing changes. Production companies of many different kinds have emerged: influential firms such as Filmax and Mediapro; producers of experimental films, such as Eddie Saeta and Kaplan; those who seek to work in co-production as a solution which can enable them to produce films that they consider to be worth making, such as Messidor or Massa d’Or, to name but a few. Thanks to the contribution of film schools (which have also created their own individual styles), today’s film professionals are better trained, and many work in the film world outside Catalonia. Our actors and actresses also work outside our frontiers. Television has ceased to be a second-class option to become a high-quality means of expression. A genuine Catalan cinema of fantasy, documentary and animated films has come into being. And the Catalan Academy of Cinema has been created to encourage all this rich variety of filmmaking creativity in our country.

Àngel Comas

Film journalist and historian

February 2009